HOSTED BY: https://fatmtnbike.com

TODAY'S RIDE

A ride between resting places

You might be familiar with the great adventure articles Tom Owen has written for us in the past; stories of his bikepacking trips through Spain and England, and his exploration of brutalist war memorials in what was once Yugoslavia. Now, Tom is back with another inspiring adventure article, this time about a week-long ride, from central Spain to the country’s north-west coast, linking two places of rest. Take it away, Tom.

***

Two places of memorial. 800 kilometres in between. This is the story of a voyage between resting places.

The first is the Valle de los Caidos, or ‘Valley of the Fallen’. It was built by General Francisco Franco, ostensibly as a monument to the dead on both sides of the Spanish Civil War. In reality, it was built with the labour of political prisoners – enemies of the Franco regime – and the monument saw many thousands more fighters from the winning Nationalists’ side commemorated than the defeated Republicans.

Any notions of bipartisanship were ultimately quashed for good when Franco died of complications related to old age at 82. He was buried at the Valley of the Fallen, the first person to be lain to rest there who had not died during the civil war. If there was doubt before, now it was certain; the Valley of the Fallen was a gigantic monument to Franco’s own brand of fascism, which he dubbed ‘National Catholicism’.

I wanted to understand how Spanish people see the Valley today. The two Basques I asked said were it not for the fascist origins, the monument would be among Spain’s greatest marvels. They told me they hated Franco and preferred not to waste much time thinking about anything related to his legacy. A Catalan told me they should destroy the whole thing, that it was a national disgrace for the Spanish government to still be funding the upkeep of such a monument. A Valencian said it should be reframed as a monument to the Republicans and other prisoners who were forced to help build it, and the ones who suffered under Franco’s rule.

There are doubtless still Spanish people who believe the monument should be kept exactly as it is. There were many who fervently opposed the exhumation of Franco’s remains, right up until they were removed in late 2019. Spain, like most European countries, still has its fascists. And so it was with trepidation that we visited the Valley, not wanting in any way to glorify this man, while still wishing to see the monument. To stand beneath the world’s largest Christian cross and try to understand what sort of place it was in the present day.

The second resting place, some 800 kilometres away on the wild Galician ‘coast of death’ – so named for the navigational difficulties it proposes, chaotic weather, and frequent shipwrecks – is the Cementerio de los Ingleses, ‘the Cemetery of the English’. In 1890, the British ship the HMS Serpent sank off the coast and all but three of its 176 crew were killed. The Galicians rescued the survivors, buried around 140 bodies that washed up on their shores, and built a small cemetery.

Nobody asked the people of Galicia to do this, but the British Navy thanked them after the fact – sending gifts to the nearby villages Xaviña and Camariñas. You can still go and look at the barometer the Navy sent to the latter village; it is on the facade of a house near the port. The wreck led to the first known use of the term ‘coast of death’ – at least in English – to refer to this part of the Spanish shoreline.

First learning of this place’s existence at the very beginning of the coronavirus pandemic courtesy of Giles Tremlett’s wonderful book, Ghosts of Spain, I knew immediately that I would visit it one day. The ship had been on its way to Sierra Leone, a country that holds a special pull for me personally, and the very creation of this cemetery seemed to speak of something I have always noticed in the character of Spanish people: a deeply-felt humanity.

1. How to live forever

Our first day of cycling took us from central Madrid to the Valley of the Fallen. The cross really is very large, almost comically so in a dark sort of way. You can see it from 20 kilometres away – and even from there it dwarfs pretty much everything else. It’s only as you reach the foot of the climb that your eye is able to pick out the basilica below the cross. And slowly as you grind up the hill, the details flash in and out of your eye-line.

After walking around outside on its vast esplanade feeling discomfited and awkward, we descended from the monument – the climb to the basilica and cross is no joke, some six kilometres at 9% – and rejoined the road to A Coruña, camping next to a font in a pine forest above a town called San Rafael. After that strange and stilted introduction to the trip, came the headwind days.

There are some moments on the bike which feel as though they’ll never end. Ploughing onwards into a gale as you battle uphill, then cresting the summit to discover it is twice as strong on the descent – effectively forcing you to pedal hard just to keep moving downhill. This would be such a moment. Every metre and mile must be fought for, the horizon never seeming to come any closer.

This was the experience of the first two days on the Castilian plain; dead straight roads, an unflinching wind, an almost total lack of petrol stations. The few dusty towns along this road north-west have the same liminal feel one experiences at international borders. An air of waiting for the next place.

And then, by contrast, there are the moments that feel instantly crystalline, the ones you will carry with you to the grave. Moments unforgettable, of which every sensory detail can be called to mind – even years after the fact. The slow crunch of twigs, the rasp of pine needles trapped between a back brake and tyre, the flickering light between trees. These moments come mostly at the edges of the day. The first hour’s pedalling and the last. When the sunlight becomes golden and soft, a fresh and precious resource instead of a determined enemy like it is at midday on the plain.

By oscillating between these two modes, it begins to feel as though riding bikes will make you live forever. Every 12 hours on a trip like this feels like it lasts for 40.

Pandemic notwithstanding, the Spanish are on course to become the longest-lived people in the world, outstripping even the Japanese by 2040. Why is this? Most studies into the phenomenon agree that it has to do with food; plentiful fruits and vegetables, meat and alcohol in moderation. But there’s another factor too, less easy to prove with statistics but far more emotionally persuasive. It is the other F – family.

Older people in Spain remain a part of their family unit, helping to look after their grandchildren, often living within the same household, or a stone’s throw away. This enduring connection is a powerful one, and it’s easy to see how a continuous link with ones descendants can provide a real raison d’être in the here and now.

It also feels to an outsider as though Spain has a stronger sense of the social contract than other places. Even things as simple as eating lunch each day on a bikepacking trip have an air of egalitarianism. The menu del dia is a fixture of Spanish food culture, providing a slap-up midday meal with two courses – sometimes a dessert too – for about €12, or a little bit more than £10. The menu del dia is usually available Monday to Friday, making it the popular option for those on a working lunch.

You will read various explanations of why so many restaurants in the country offer this – some people will even tell you it is legally mandated – but in reality, in modern day Spain it is not obligatory to provide a ‘menu’. It does, however, have its roots in one of the fascist Franco regime’s more socialist ideas.

In the 1960s, the government passed a law making it obligatory for restaurants to offer one reasonably priced plate of food or a meal, on at least one day of the week. The law is said to have been passed so that even the poorest in Spain could have the dignity of a ‘meal out’ every now and again. A less charitable interpretation of the law’s creation points to its benefits for tourism; the law was passed by Franco’s Ministry of Information and Tourism after all, not the Ministries of Labour or Industry. This ‘one plate’ morphed into the daily multi-course meal you can find today.

Regardless of its origins, the law is no longer in effect. Now, to the great delight of hungry bikepackers, restaurants from metropolitan Madrid all the way to provincial Galicia still offer a cut-rate midday meal. They needn’t, but they do. They could charge much more for the meal than they currently do, but most choose not to.

Whether it’s food, family, or some other ineffable factor, the Spanish live a long time – and seem to enjoy themselves while they do it.

2. Farting in sleeping bags

Each morning on a bivouacking bike tour follows the same approximate routine.

The first tendrils of dawn creep into the world.

The light might break through your defences and rouse you, particularly if whichever means you have chosen of blocking that light has fallen away in the night. I favour a woolly hat pulled down over the eyes, because it has the secondary benefit of keeping one’s ears warm.

Do not be hasty; there is no need to get out of your bag just yet. Particularly if no one else is stirring.

Wait for the sun to rise a little higher, while making preparatory explorations with one arm outside of your sleeping bag. Did you leave any food last night that might make for a suitable pre-breakfast snack? Smarties, bread, a cold cooked sausage? It’s all fair game. It’s all grist to the mill.

Drink all the water within reach. Gulp it down like a camel at an oasis. It will be crystal cold and deeply refreshing. You have been dehydrated for four days.

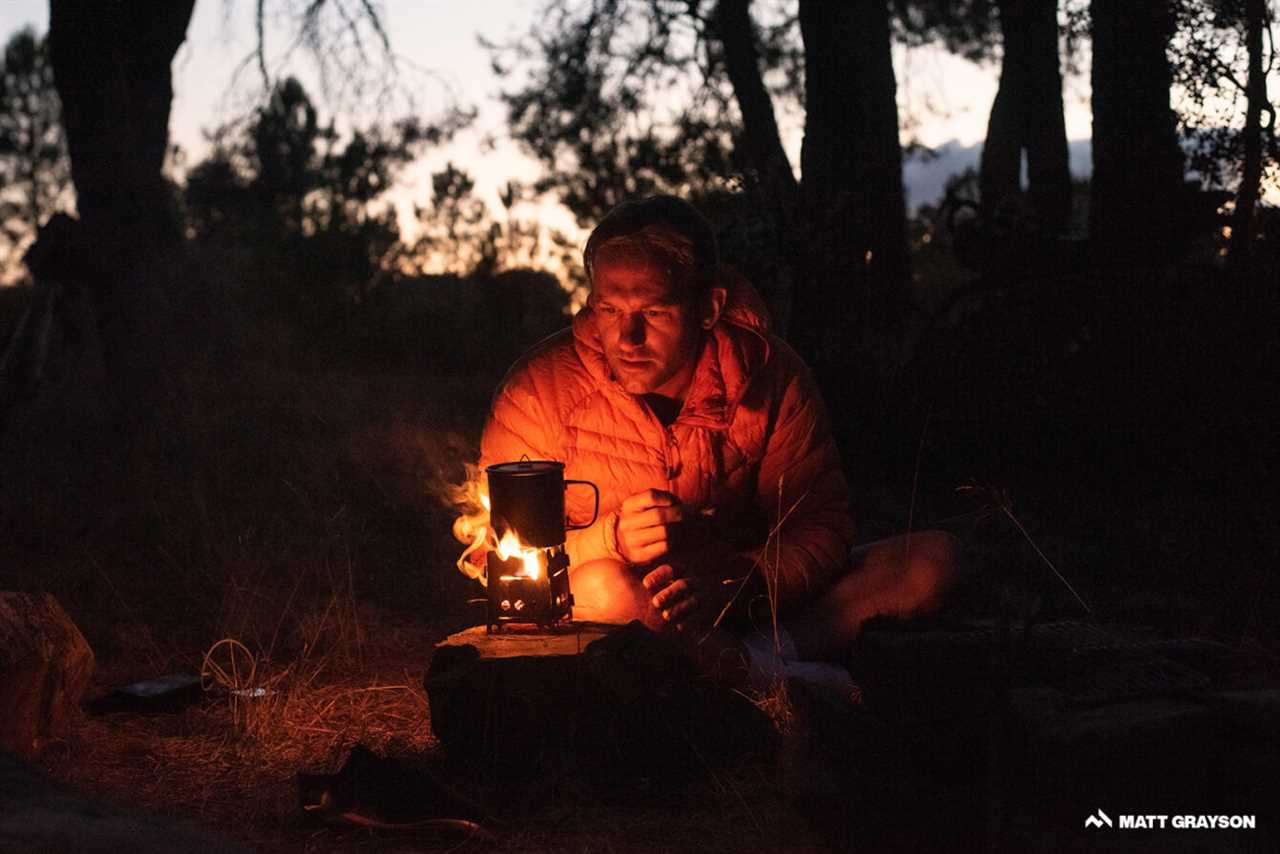

Over a week, one member of your party will become the camp coffee brewer. Usually, it’s the one who has the greatest caffeine dependence, the one that simply can’t get going without a cup of joe. It might also be whomever has the worst sleeping bag, and relies on the heat from the small twig stove to warm themselves through each morning.

Do not get out of the bag until this person has begun the coffee preparations. There is nothing to be gained by an early exit. Check again to see if there’s anything else you can eat nearby.

When the tin lid placed on top of the boiling water pot begins to rattle, grudgingly get out of your bag. Feel free to break wind at this point. And at any point in the preceding or following steps.

Shamble over to where the coffee is being brewed.

Drink the proffered cup and heap lavish praise upon the brewer. Have they become more handsome overnight? Surely, there has never been a soul so gentle as theirs! You can’t layer it on too thick at this point. You need to keep this schmuck sweet for a couple more days, after all.

By this stage, one can even offer to help – safe in the knowledge that all the work has already been done.

Once the coffee is poured and the first mouthfuls are filling your belly with happy, enervating warmth take a moment to reflect. This is the least exhausted you’ll feel for the whole day.

Once camp is packed up, head for the nearest cafe-bar on Google Maps. Drink two more coffees and order four of any pastry-type products you can see. Make use of their facilities. Apply suncream. Order four more pastries. You and your colleagues should waste at least an hour here.

Now, you are ready for a day of bikepacking.

3. We’ve gone on pilgrimage by mistake

A route that passes through Galicia is almost certain to intersect the Camino de Santiago, the 1,300-year-old Christian path of pilgrimage. In fact, for about a day and a half, our wheels carried us along some of the Via Francesa, ‘the French Way’, the most trafficked of all the many different routes to the cathedral at Santiago de Compostela.

On a morning outside Astorga, we picked up the road that the Camino now runs alongside, and as we glided ever closer to the Montes de Leon – a subsection of the Cantabrian system – we rolled through old villages advertising rooms for pilgrims. As we turned a corner and spotted a tottering old church steeple at the far end of town, a kettle of swallows swarmed in the air above our heads. It’s a moment that felt unlikely to have changed much in the 1,300-year history of the Camino.

Yes, we were riding modern road bikes laden with newfangled bikepacking equipment and checking our GPS devices for the right way to go through town – but the essence of this moment felt like something outside of time. The flicker of the wings, the watery morning sun that was working up to another belting afternoon. These are sensations experienced by pilgrims more than a millennium ago.

On, on we went, deeper into wondrous Galicia, always spotting the iconic blue signs with the yellow scallop shell. There are some 300,000 visitors to Galicia every year who come because of the Camino and the roadside is busy with walkers.

There are many who are doing their pilgrimage by bike too. Mostly they ride mountain bikes. Our loaded road bikes just about survived in the few instances where we accidentally found ourselves on the jagged rocky surface of the Camino itself, but you wouldn’t want to do it day in day out with anything less than a gravel-specific rig.

For one’s journey to qualify as a Camino pilgrimage, one must walk 100 km of the Way, or ride 200 km of it. Quite what “qualify” means when you’re talking about a devoted act of service and sacrifice to an all-seeing deity, I cannot say.

During this part of the ride, every person we met along the way would greet us with a “buen camino”, a simple good luck wish traditionally exchanged between pilgrims.

It feels a little bit fraudulent to be offered this greeting of fellowship because we are not truly pilgrims. This ugly duckling feeling intensified in the square outside the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela itself, us a quartet of lifestyle-vagrants, voluntary vagabonds, surrounded by people at the end of a truly definitive journey in their lives. To be in that square was not the end-point of anything; for us, that would only come at the end of the world.

4. Brain jelly

When you ride bikes long distance over multiple days, something strange begins to happen to your faculties. The thoughts that pass through your mind as you pedal onwards become flabby and shapeless, gooey even. They stick in your head when they would previously have flitted straight through. They develop into fixations, so that you spend an hour of silent pedalling trying to remember the lyrics to a children’s TV theme tune you loved as a kid; trying vainly to call forth this useless trivia. Then, when you stop pedalling, the thought is gone entirely, replaced with a desperate need to drink Coca Cola and eat an ice cream.

Your emotional responses are also sharpened, intensified, but triggered by wildly disparate inputs. I saw a dog on the sixth day in Spain, a big brown one of indeterminate breed. The thought “I love dogs” passed through my mind, and the strength of feeling that this observation provoked was enough to bring a tear to my eye.

It wasn’t a particularly special dog, it didn’t look like some cherished pup from childhood. It was just a dog. The essential qualities of this dog had not substantially changed, but my mind’s response to the stimulus had.

Over long hours in the saddle, “I love dogs” can become the most profound thought in existence. What you’re essentially creating inside your skull is a brain jelly, a lumpy mind soup, a viscous and unpredictable gumbo.

Imagine then the crashing emotional tidal wave that comes at the end of such a journey. The last moments of the ride to the Cemetery of the English. The nature of the coastal terrain in Galicia – many ups and downs, plenty of tree coverage – means you do not see more than a faraway flash of the Atlantic until you are right upon it. You hear it first, in fact, as the steep tarmac climb from the village of Xaviña gives way to gravel. The pine trees planted in tight rows fall away near the top of the small ridge, to be replaced by scrub.

And then finally the ocean is revealed, the inky blue Atlantic, its furious waves battering at the magmatic shore. The rocks themselves, like flung tendrils of some impetuous creeping plant wrought in granite not green.

About 20 miles south is Cabo Fisterra, Europe’s westernmost point and where ancient people like the Romans believed the world ended. Looking around at this improbable place, it is easy to understand why. It feels like the ragged fringe of a piece of cloth, the very edge of the fabric of reality.

It’s only 120 metres of descent down to the shore and the cemetery, and it takes no time at all.

The cemetery is a memorial to the lost lives of 173 sailors from the United Kingdom. The mind recoils from imagining the terror they must have felt that night, as the ship ran aground and was battered to pieces by the storm. There is a first-hand survivor’s account by the sailor Edward Burton, a section of which is copied here below. He references another of the trio of survivors, Onesiphorus Luxon.

Luxon and some of our shipmates who were swept away by the swell succeeded in gaining the rocks, but Luxon was the only man of them who was able to hold out against the force of the sea, and to reach the shore, it is true, in an almost lifeless condition. A wave carried me away and threw me ashore near to where Luxon was. We looked back and saw a horrible sight. There was a shapeless mass of men struggling for life, and being hurled one against the other by the great seas.

It took around an hour for the HMS Serpent to be destroyed entirely by the waves. They launched lifeboats, but these were immediately carried away by the sea and smashed against the rocks. Finally the ship’s captain gave the order for every man to try and save himself.

It’s hard to explain what it felt like to stand at the cemetery that commemorates their deaths, after riding so far to reach that point – and having started in a place haunted by such awful memories. Here instead is a place that stands in defiance of the values of fascism, the rejection of the foreign most of all. It is humble and small. The outer wall is not even shoulder height. And yet it is a mighty place, a collection of stones that have stared down the Atlantic for a century.

This is a better kind of immortality, a noble human act that emerged from the wreckage of disaster.

Gallery

Day One: The Valle de los Caidos.

Valle de los Caidos.

Day 2: Rolling out from the day one camp spot just outside San Rafael.

Riding part of the Camino de Santiago on Day 2.

Day 2: Cooling off in the Rio Pisuerga in Simancas.

Day 3: Not your typical bike and sunflower photo.

Cooking up at the Day 3 camp spot outside Astorga.

Day 4: Taking a rest by the Cruz de Fierro on the Camino de Santiago.

Day 4: The descent to Ponferrada.

Molinaseca.

Day 4: The Castillo de Ponferrada.

Day 4 was the start of the Galician stage of the journey.

Day 4: Obstacles on the way to Triacastela.

Rolling out on Day 6. The night before had been spent in the grounds of an old Sanatorium just outside Cesuras.

Just one of the many leg-sapping short, sharp, forested climbs on Day 6 in Galicia.

Day 6: A short way from the Cemetery of the English sits the Faro de Cabo Vilán, Spain’s first electric lighthouse built in 1896, six years after the sinking of the HMS Serpent.

Day 6: The gravel road that hugs the Atlantic Ocean from the Cemetery of the English.

Day 7: Contemplation in the square outside the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.

The route

With thanks to the Historic Photographs & Ship Plans department at the Royal Museums Greenwich.

By: Tom Owen

Title: A ride between resting places

Sourced From: feedproxy.google.com/~r/cyclingtipsblog/TJog/~3/4r5JFwlDYbY/

Published Date: Wed, 20 Oct 2021 01:10:57 +0000

___________________