HOSTED BY: https://fatmtnbike.com

TODAY'S RIDE

A journey into the bike industry’s doomsday vault

The last sanctuary of outdated bike tech – the unlikely outcome of a collaboration between government and industry – lies buried in a mountainside, deep in the Arctic Circle.

This is its story.

SVALBARD, NORWAY (CT) – It’s -14 ºC (6° F) in Longyearbyen, and little flurries of snow dance in the Arctic breeze. The entrance to the vault – looming obelisk-like from the hulking mountain it is tunneled into – is floodlit, casting angular shadows against the snow. There’s a makeshift stage set up on the right for this end-of-times media opportunity, but nobody’s paying much attention to the dignitaries, because the northern lights are flickering, a ghostly radium stain between the clouds.

It’s really, really fucking cold and, not for the first time, I find myself wondering what the hell I’m doing here.

‘Here’, if you can believe it, is on assignment in the Svalbard archipelago, a long-haul flight and a couple of short hops from Melbourne to Oslo to Florø to Tromsø to here, 78° North – to tell the story of the cycling industry’s last hope for survival.

It’s a more complicated story than that, of course. Because it’s also a tale – years in the making – of a woman’s love for a bike, and of an international diplomatic effort that brought sworn enemies together for the first time.

All of that leads to this point, where we stand half-frozen outside a vault in the Arctic Circle, far away from the ravages of consumerism, with a distant hope that the history of bike tech might be saved.

The Noah’s Ark of cycling

How did we get here? Great question. It goes like this.

The year is 2022, and the twin perils of a boom in bicycling and a COVID-accelerated supply chain collapse have led to cycling’s imperilment. Prices are jacked up into the stratosphere – if you can get anything at all. You want an aluminium bike? That’s cute; the raw materials are back-ordered into the next decade. Perhaps something in titanium? Sanctions against Russia have locked those behind the new Iron Curtain for the foreseeable future.

And that’s before we get to the pre-existing disaster that they – we – gladly built for ourselves. A cursed maze laced with traps: subtly different integrations and new standards that made repairing an existing bike a virtual impossibility even before COVID, before Ukraine, before this.

So that’s the problem. But what were we going to do, throw up our hands and walk away from our bicycles, because we couldn’t get BB92 parts anymore?

Hence, the vault. The Global Cycling Archive.

How a broken bike built a vault

The story of the cycling industry’s doomsday vault is vast, but it’s written on a human scale, too. That part begins with a politician and a 2012 Trek Domane.

Norwegian prime minister Erna Solberg loved her bike until she couldn’t ride it anymore. “I can picture it now,” she says, her blue eyes staring intensely at me. A thick Bergen accent – or emotion – gnarls her words, as she traces out her bike’s angles with her gloved hands in the air. Muscle memory. “Just like Cancellara’s. White, black and red. And then … then it was gone.”

I knew something needed to be done.

Erna Solberg

Solberg’s a conservative politician, not a bike mechanic, so when her IsoSpeed decoupler got a knock to it she didn’t have the vocabulary to articulate what was happening – something just felt off. She’d hit the cobbles on her lunch rides around Oslo, finding peace in an intermission between parliamentary sittings, and something went – and I quote Solberg herself here – “clunk”.

With her security detail in tow, Solberg was off to the mechanic. “They couldn’t get the part [ed. pivot axle] to repair it,” Solberg says, her voice catching a little at the recollection. “What I did next is not, perhaps …” – here a lengthy considered pause – “… fiscally responsible, but I knew something needed to be done. I thought I knew where we needed to go.”

The answer lay in Svalbard in the country’s far north, just 1,000 km from the North Pole – an archipelago of barren rock and snow, where humanity has etched out a fragile hold for itself.

Diplomacy and dystopia

The Svalbard Seed Bank was established in 2008 by the Norwegian government while Solberg’s predecessor Jens Stoltenberg – now security ceneral of NATO – was the incumbent PM. It was envisaged as a kind of Noah’s Ark for the world’s crop diversity, and, some suggest, a mea culpa for Norway’s collective guilt as a leader in the fossil fuel industry.

The Seed Bank was to be a special place, hollowed out of the permafrost – a place where mung beans and mangosteens could coexist, peacefully, together at last.

Regimes change. When Solberg saw the writing on the wall for her beloved Trek Domane, she realised that she was the canary down the coalmine for an industry in peril. She lists out the casualties of cycling’s endless march forward: “If your external battery dies and you have the Shimano 7900 Di2, what do you do? What about the hardware for a first-generation Giant TCR with the integrated seat pole [ed. post]?

“And it isn’t getting any better,” she says, before launching into a lengthy diatribe about internal cable routing through the headset.

A breeze whips across the tundra, sending Solberg’s hood flapping in the breeze. Her eyes seem to well up – from the cold, perhaps? Or the thought of millions of loyal bikes condemned to scrap? And then she turns to me, leans in, almost hissing in my ear through the flap of my stupid-looking hat. “It shouldn’t have to be this way,” she says.

There was, Solberg knew, space at the Seed Bank. “Jens built it quite big, but he didn’t realise how many plants were already extinct,” she murmurs with a hollow chuckle. “We have space here for 4.5 billion seeds, but I learnt that seeds are actually very small. There was a whole network of bunkers off the main hall – plenty of space for whatever bearings and hubs and stems or whatever we could find.”

Solberg and her diplomats embarked on an urgent mission, equal parts diplomacy and humanitarian, to save the discontinued cycling products of the world.

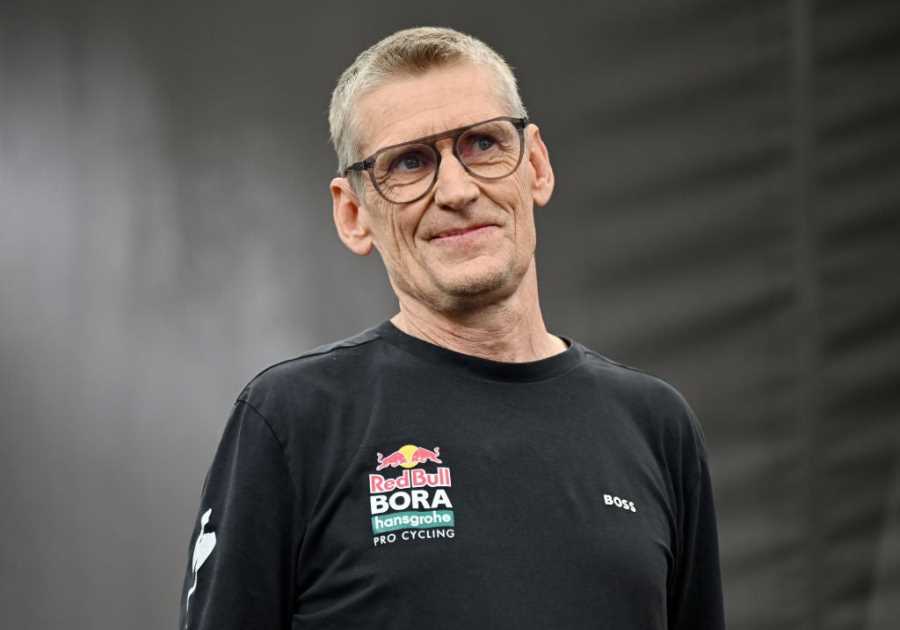

In boardrooms from Chicago to Sakai City, Waterloo to Morgan Hill, the industry slowly came to an accord.

“We realised that we were tearing ourselves apart,” Specialized founder Mike Sinyard explains, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with former nemesis, Trek CEO John Burke. “We didn’t have the foresight that we do now. If a Zertz insert dies, so does a first-generation Specialized Roubaix,” Sinyard says, bluntly. “We need to do this. For the bikes. For all of us.” With his mitt, Burke dabs a tear out of the corner of his eye.

A helicopter lands, cutting the speeches short and sending a swirl of Nordic pow blasting into the faces of the assembled CEOs of the cycling industry. Boxes are unloaded, and carried solemnly into the mountain. We follow them in, walking slowly behind like mourners behind a hearse. Fluorescent lighting and concrete walls stretch their tendrils into ancient stone. Box after box of rim brake pads and eight-speed drivetrain parts and 650C rims are placed – like the sacred objects they are – on metal racks designed to survive the end of days.

Outside, the sky dances to its ghostly song.

The wake

The night’s a blur. Back in Longyearbyen town, we retire to a dive bar in a surreal cluster built of shipping containers, full of grizzled locals and industry bros in trucker hats and puffer vests. I grab a seat at the bar, and sink a pint of Mack – the best beer north of the Arctic circle, which isn’t saying much. I sink another and listen to the rising and falling blizzard of industry gossip around me.

Someone from Rapha’s in my ear talking about a vegan merino blend they’re working on. Josh Poertner has found a corner booth with a powerpoint and is 3D-printing tyre sealant, writing calculations on the steamed-up window with his finger. Behind me, a guy from Campagnolo is telling a guy from Cannondale that they’re bringing back the Mirage groupset; he wants in on OEM supply, but Mr Cannondale’s not buying it. Another pint and someone from Sturmey-Archer is dancing on a table.

My last memory before I black out is a group sing-along of Queen’s ‘Bicycle Race’ led by Bonnie Tu.

The next day, heavy-headed from akevitt I barely remember drinking, I stumble across salted gravel and up the steps of a small plane that will take me away from cycling’s Noah’s Ark. As we speed down the runway, I catch a glimpse through the window of a ragged polar bear prowling the perimeter. I think of the guards at the vault with their rifles, holding back nature in the defence of 11-speed rim-brake eTap shifters.

Not for the first time, I’m struck by the nagging fear that it’s all futile. We sowed this crop. Maybe it’s only right that we reap its bitter harvest.

The plane seems to waggle its wings in farewell as it banks over the mountain. There, lit by a green glow through the gloomy half-light, I can see it: the monolithic spike above the town where hope will live – or die – for the outdated tech of the cycling industry.

Find out more:

Key founding members of the Global Cycling Archive will be participating in a live Q&A from now until 12pm, Friday April 1. You can participate here.

By: Iain Treloar

Title: A journey into the bike industry’s doomsday vault

Sourced From: cyclingtips.com/2022/04/a-journey-into-the-bike-industrys-doomsday-vault/

Published Date: Fri, 01 Apr 2022 00:04:07 +0000

___________________